In June 2020 the Danish parliament passed a Climate Act that set the target to reduce Denmark’s emissions at 70% in 2030 (to compare, the Dutch government passed their Climate Act in 2019 with a 49% reduction target). This courageous 70%, however, is not the most high-profile aspect of the Danish Climate Act. Within their Act the Danish politicians commissioned a Climate Citizens’ Assembly to receive advise from citizens on how to achieve this target. “As far as I know, there is no other climate assembly that has been made by law”, says Kathrine Collin Hagan, senior project manager at the Danish Board of Technology and one of the lead facilitators of the Danish Climate Citizens’ Assembly.

This interview is part of a the international project Climate Citizens’ Assemblies: learning with, from and for Europe, initiated by Bureau Burgerberaad and Pakhuis de Zwijger, together with Extinction Rebellion NL and De Transitiemotor. Via various in-depth interviews, European keyplayers share practices, reflections and personal experiences with Climate Citizens’ Assemblies . In this second edition, we reflect with Kathrine Collin Hagan on the Danish approach, that relies heavily on consensus and trust between citizens and politicians.

What kind of organization is the Danish Board of Technology (DBT), and what role did they play in the Danish Climate Citizens’ Assembly?

“The Danish Climate Citizens’ Assembly was initiated by the Danish parliament, who hired the DBT as facilitator of the Assembly”, says Kathrine. “The Danish Board of Technology has a long history in deliberative democracy…It used to be an institution set up by parliament to advise them on technology and democratic development. As such, we developed the consensus conference method and have worked with it for decades.” The consensus conference method can be seen as a kind of forerunner of the Citizens’ Assembly method. As Kathrine explains:

“It works with a smaller randomly selected group, 12 to 16 citizens, but the process is more or less the same: deliberation, dialogue with experts and development of recommendations – based on consensus. In Citizens’ Assemblies there is a larger group involved and a lot of voting, whilst with the consensus method everyone must agree. The principle is, if this diverse group of citizens can agree, the whole population will support it. So, no voting, no compromise, no disagreement. Only consensus.”

Interestingly, Kathrine commented that in the 1980’s the Danish parliament had even institutionalized this method, yet it somehow went silent for 10 to 15 years. Currently, with the introduction of a Climate Citizens’ Assembly, it has become hot and happening again.

Did you use the consensus method in the Climate Citizens’ Assembly?

“I think we had a special Danish approach”, Kathrine explains, “we built on the same internationally acknowledged principles as other countries, but we adopted elements of the consensus method into it – of which we knew they would work well in Citizens’ Assemblies”.

The Danish approach started by a selection of 99 citizens, who were selected by using a stratified random sampling method. Next, smaller ‘editorial’ groups were created our of the selected 99 participants. These groups consisted of 5-6 people and they all worked on subthemes related to tackling climate change, like electric vehicles, popular engagement, or other issues chosen by the assembly members. The editorial groups had the task of developing recommendations on their specific subthemes, and – here comes the Danish addition – reach consensus on those recommendations. Finally, during the last weekend, the entire 99 members assembly voted on the various proposals made by the editorial groups. In this manner, they combined the Consensus Conference and the Citizens’ Assembly method.

Contrary to the recommendations from Poland in our previous interview, the Danes did not ask about attitudes toward climate change in their selection process. On this topic Kathrine commented: “No, we did not ask them about their attitudes toward climate change, I do not think it is very Danish to label people. Besides, if you have a randomly selected group, I trust they would differ in beliefs”.

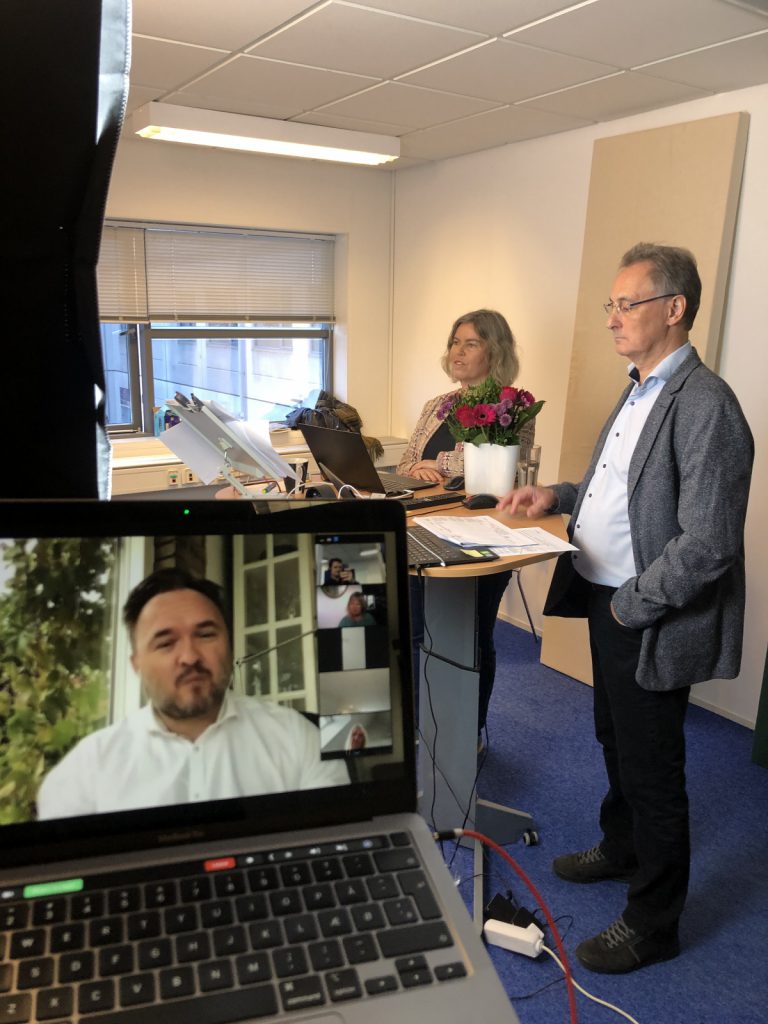

© Aske Palsberg. Kathrine Collin Hagan (left) and Lars Klüver (right), lead facilitators of the Climate Assembly and the minister of climate Dan Jørgensen on screen, at one of the online Citizens’ Assembly meetings.

What was your experience with a Climate Citizens’ Assembly on the big question ‘help us reach our goal of a 70% gas emissions reduction by the year 2030’?

“I think the big themes give freedom for the members to think outside of the ordinary political framing”, Kathrine said. “If we told them, ‘You have to restrict yourself to transport’ they would say ‘But we can’t fight climate change that way, it has to do with all aspects of life’”.

The Danish assembly started with 100 topics and eventually the members narrowed it down to 19. One of the themes that stood out to Kathrine was climate & health issues. “That is not a regular theme when you think of climate change”, she said, “So, if you choose a theme that is broad, individual ideas can come to the fore. There is an advantage and a disadvantage. If we do it on a local level, it would be useful to narrow it down.”

How was the political follow-up organized?

“The mandate for this process can not be said to be strong, or at least, [it does] not [have] a formal strong mandate”, Kathrine said. “That is also a criticism we received from some activists. Nonetheless, the political follow-up has evolved over time: there have been two meetings between the Climate Citizens’ Assembly and the political committee, and the Assembly has been promised a report as a response to the recommendations. As this Climate Assembly has been directly commissioned by the parliament by law -as it is written into our Climate Act- there is a direct connection to the politicians.”

At the moment the recommendations of the Danish Climate Assembly are still being read by the parliament and the Assembly is waiting for their report on if, and how, their recommendations will be implemented in policy. This might be the most interesting about the Danish case. The activists’ criticism mentioned by Kathrine is a relevant concern: what does a Climate Assembly mean –even when initiated by the parliament by law– if there is no insurance of political follow-up? All the hard work citizens have put into it could become in vain, what would damage the process, the trust between citizens and government, and the future perspectives of Citizens’ Assemblies. In this case, Kathrine repeatedly expressed the citizens’ trust in the government on this topic. Apart from initiating the Assembly themselves, the politicians were also very involved during the process. It would come as a surprise, Kathrine states, if nothing would be done with the recommendations:

“What the Climate Assembly has shown is: bring 99 ordinary people in a (virtual) room, some of them not engaged in fighting climate change, and they become very dedicated. And they expressed that to politicians saying ‘We as a randomly selected group want to give you the support to be courageous, to show your political power and to act. We stand behind you’. So, I think that is a clear signal. These are just ordinary people and they found out that the solutions are there, waiting for us. Some Assembly members even expressed that they knew it was going to influence their daily life, that they were going to have to change their habits, and that they would have to sacrifice something. But they were very happy to do it. Their political message was: ‘don’t be afraid to make these decisions, just go for it’. I think that message is very important for the politicians to hear, because they are in the middle of these very important decisions, and this gives them the support to do what is necessary. That is the long-term effect.”

Do you think Denmark will organize more Citizens’ Assemblies in the future?

“It [the Climate Citizens’ Assembly] has attracted very little, too little media attention. Most people in Denmark don’t know it is going on”, Kathrine said. And media attention is very important:

“Citizens must know what is going on and that it is important they recognize themselves in the assembly. However, DBT was not in charge of this. If we would have been, we would have tried to gain more media attention. People should have the feeling ‘it could have been me sitting there and giving political input’. Media attention could play a pivotal role in this.”

Clearly, in order to give people the chance to enter the deliberative wave of Citizens’ Assemblies (and maybe develop their own (local) initiatives), they must at least know what is going on. In the Danish case, it seems hard to generate this snowball effect, as many people simply did not know about it. Moreover, the media does not only play an important role in informing people about the Assembly, it also monitors the process. If there are no people from outside the process are following and reviewing the project, the assembly might lose its credibility.

Final observations

Overall, it is safe to say Denmark has a very welcoming political climate when it comes to Citizens’ Assemblies. Aside from the initiating role of the parliament, municipalities are also very eager to hear the voice of the ‘silent citizens’ (the ones who don’t show up to voluntary participatory meetings), according to Kathrine. Additionally, she expressed good faith towards politicians when it comes to implementing the recommendations, even without an official mandate. Looking at it with an outsider’s perspective, however, there is still a lot of uncertainty: nor DBT or the participating citizens have the guarantee that their hard work will pay off, or will be discarded.

But it’s not only Citizens’ Assemblies that we should look at, Kathrine says:

“There are more methods that can establish that valuable deliberative process. The Consensus Conference, the citizens poll, citizens jury, these are all methods in the same toolbox. The Climate Assembly is not the only tool for any solution.”

This resonated with what the director of the DBT, Lars Klüver, mentioned during the third LIVECAST. He argued that the most important thing is not that an assembly’s recommendations are treated as a binding strategy, but that you establish an environment in which politicians and citizens deliberate together and establish communal trust. That they get the time to sit together and understand each other. In that area – developing mutual trust and understanding between citizens and politicians – the Danes seem to be at an aspirational place.

If you want to know more about this subject, check out our online knowledge platform ‘Climate Citizens’ Assemblies’ and join us for our coming LIVECAST session ‘Depolarizing Climate Change’.